Years ago, I find myself in Portland. I’m watching Denis Johnson talk about creating characters and I’m nursing a cup of wine, one of many, and later that night we’ll tumble and fall and cackle in the wet grass. We’ll collapse into one another, knowing that although we’ll write about this evening, this time, for tonight we resolve to simply live it. Live without documenting it. Live without recognizing the things we carry. Things like pain, grief, loss, and so much sorrow. We’re not yet thirty but the weight we bear is heavy, altogether too much for our bodies. And although we are walking crime scenes, we capture fireflies in our cupped palms. We spill cheap wine on the grass, on each other, and later we’ll collapse into bed feeling everything and nothing all at once.

But for now we talk about Denis Johnson—did he sign your book too?— and how we hope we would write as plainly and honestly as he does. What I don’t talk about is the then-famous writer who held a draft of a chapter of what would become my first book in his hands. We don’t talk about the story, we talk about drinking. How much we like it. How it’s the lover who would never abandon and leave. How it’s the one thing that will hold you close and soothe you through the dark. We trade war stories and compare the wounds. The difference being the war is one he’s waged and won—he’s sober—and it’s a battle I’ll fight for much of my adult life. I tell him that people often tell me I’m impenetrable and he nods and says he can see that.

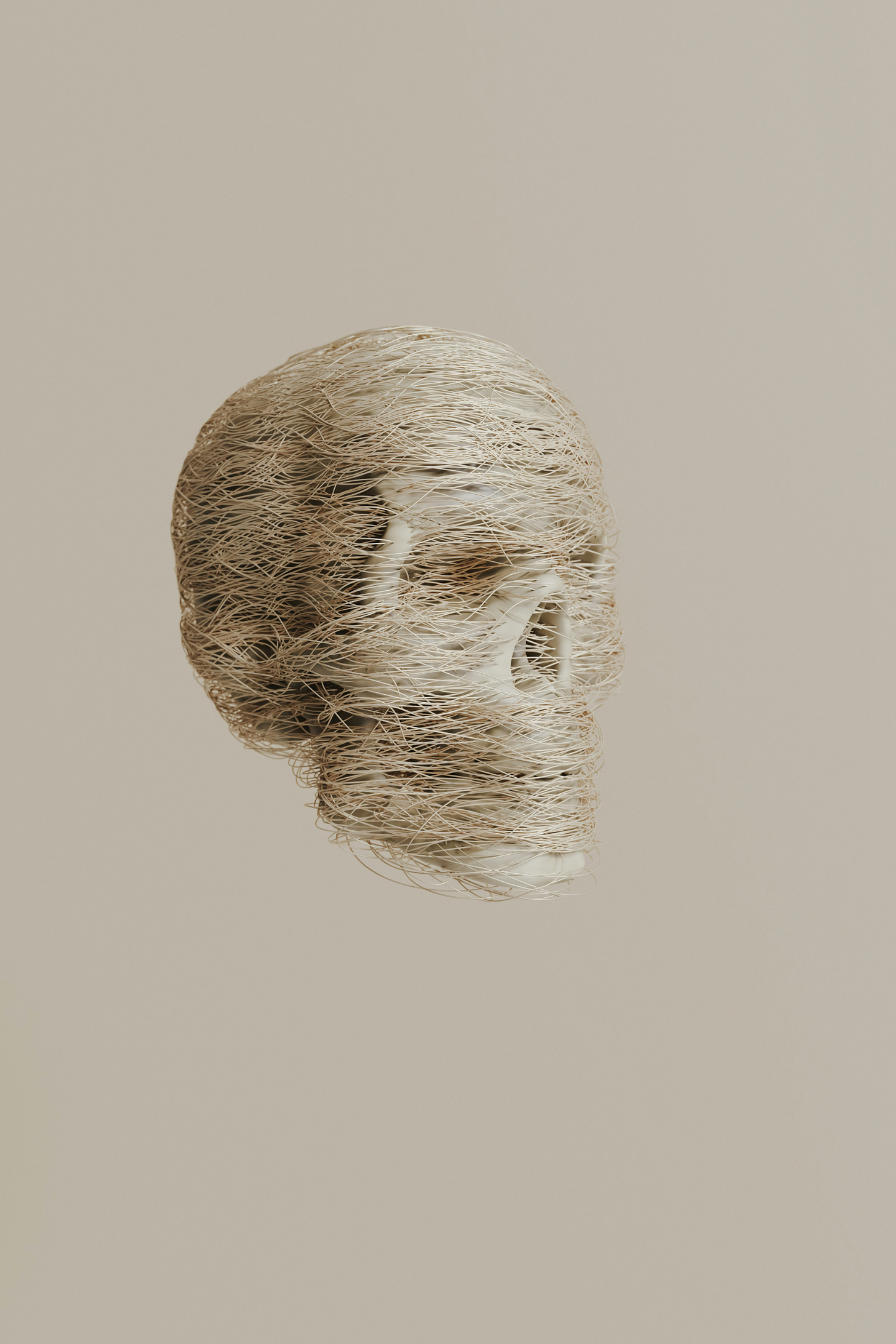

He holds a print-out of my chapter in his hands and tells me how I let people in, only a little but not too much. I give them enough to show that I feel, I’m human, but there’s a point where I hold my hand up. Stand back, please. Go away, please. He tells me I don’t let me reader in all the way and I nod and think about the happy hour in a few hours and how the chapter he’s marked up will become the confetti I toss into the air. The words I write will rain down on me.

Years later, I’ll have coffee with someone I met at that conference and we talk about Denis Johnson’s passing. How it’s forever strange that people come into our lives and they’ll die. Gone, poof—full stop. He was once alive, standing in front of us, talking about dialogue, and now he’s in the past tense. My friend and I talk about his last book, The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, and what a departure it was from the verve that was Jesus’ Son. Jesus’s Son was alive, bracing, kinetic, a pulpy heart still beating in your hands. And his final collection, published posthumously, was quieter. Contemplative. A man who once wrote of the mess and wreck of life while it was happening now writes from a place of emotional calm and perspective.

It’s the difference between an alcoholic’s shaky hand—in want of the drink—and a steady one. It would’ve been a beautiful thing to see where Johnson’s work would’ve gone had he lived a little longer.

Part of me misses the mess. What it was like to be young with all the possibility laid at your feet. Oh, the places you could go, you tell yourself. And life is about traveling to those places until the possibilities become smaller while the want looms large. You find your time has passed—the kids, it’s their time now—you can’t help but crawl back to the music and memories of before. And how a song could take you back and you could smell and see and hear the world as you once knew it before everything you know now. And perhaps it’s the space between the not knowing and the knowing I’m desperate to occupy. The space between the mess and the calm. The moment when you just begin to notice the signs of age but you’re not there yet, you tell yourself. You still have time. So much of it.

You’re still kind of young. Even if the world, you’ve noticed, has become louder than it once was and could everyone just turn the volume down? Could everyone be quiet, please? My god, you sound like a Raymond Carver novel and there go the lines that spider your face and the grey that sprouts like weeds and the body that hurts more than it used to. How is it that you can feel everything as your body ages? How you can register the blood as it moves and the bones that click as you walk and the parts of you that have started to rot in the parts and places no one sees.

It occurs to you that the stories you write are the skins you shed, the versions of you that have come and gone over time. And while the late Joan Didion would have us be on nodding terms with our former selves, all I can do is wince and cringe. Though, there are moments. The wet grass in the gloaming during that one summer in Portland. The first time, the second time, and the third time you quit the drink for good. The books you write that you’re proud for having written but belong on a shelf because you’re a different woman now. A woman who knocked down the tower and all the walls and felt what it’s like to let everyone in.

There are moments when you realize age and writing are both about the walls you build and tear down and the hope and love and ache that occupies the space between the two.