Yes, There’s a Difference Between Confessional Essays & Journaling

One focuses on craft, the latter centers on catharsis.

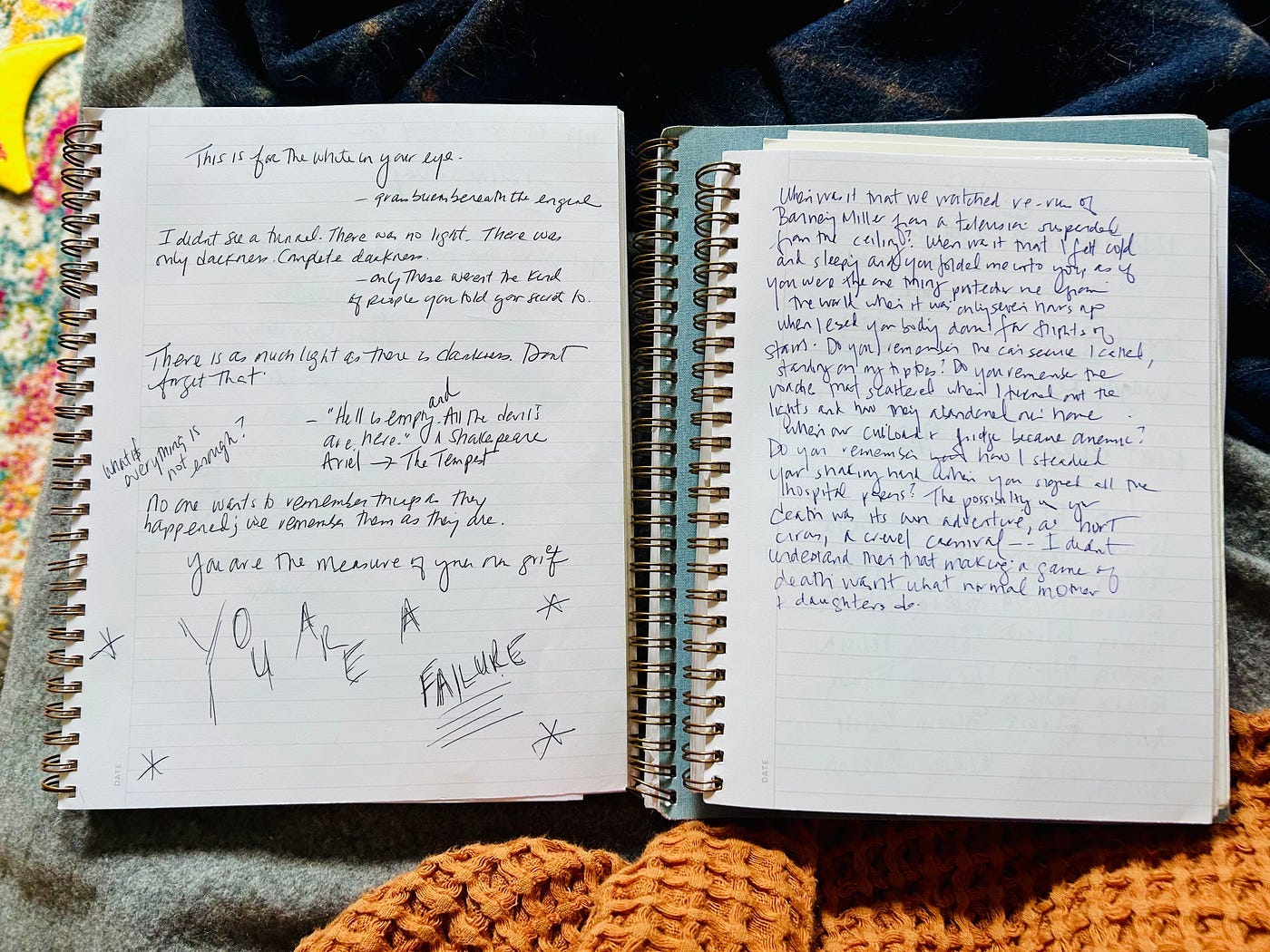

Journals are a safe house for feelings. Before we typed our emotions, we held notebooks in our hands. A refuge from the everyday, our journals were an escape, a place where we could be the star of our own story. We were the keeper of our dramas and intrigues, the documentarian of our lives. Our journals were the space where we could shout: this happened to me.

Beyond confession, journals also provide a space for experimentation and play. Virginia Woolf, who left behind 26 volumes of writing upon her death in 1941, “approached the diary as a kind of R&D lab for her craft” — an essential tool for the writer seeking to hone their voice and style. Many of her entries were the foundation of what would be come her most famous works of fiction and narrative non-fiction.

More than a mere tool of self-exploration, however, Woolf approached the diary as a kind of R&D lab for her craft. As her husband observes in the introduction to her collected journals, A Writer’s Diary (public library), Woolf’s journaling was “a method of practicing or trying out the art of writing.” (source)

For many years I kept a journal and it was a haven for my observations and experimentations with language. I’d have an image in my mind or a metaphor I wanted to play out and I’d use my journal as a place to not only jot down what interested me, but also a place where I could learn how to translate those observations into prose. And maybe those images would turn into a story that would turn into a book, or maybe not. What was key here was learning by doing without the risk of falling flat on my face.

When I re-read my journals, there exists no rhyme of reason. They’re a haphazard scattering of notes, words, phrases, images, and character sketches. A series of sputtering stops and starts. Ideas that took root or were abandoned. They were the seeds that may or may not bloom, but they were a crucial step in my writing process. I learned how to deconstruct sentences and rebuild them. And I learned how to manipulate language to offer my readers something new.

Never would I have found my voice had I not had a safe space to play.

But journals are the seeds, not the plant. They are the beginning of the story not the whole of it. Simply put, journals are about turning our gaze inward while art is the means in which that gaze expands outward to cultivate connection and create relatable (or un-relatable) human experience. Sylvia Plath, perhaps one of the most famous confessional poets, held a disdain for navel-gazing. In a famous 1962 BBC interview she says,

“I think my poems immediately come out of the sensuous and emotional experiences I have, but I must say I cannot sympathise with these cries from the heart that are informed by nothing except a needle or a knife, or whatever it is. I believe that one should be able to control and manipulate experiences, even the most terrific, like madness, being tortured, this sort of experience, and one should be able to manipulate these experiences with an informed and an intelligent mind.

I think that personal experience is very important, but certainly it shouldn’t be a kind of shut-box and mirror looking, narcissistic experience. I believe it should be relevant, and relevant to the larger things, the bigger things such as Hiroshima and Dachau and so on.

And if you’ve read Plath’s journals you could see the germination of the poems that would become her best work, Ariel. You could see her anger, her helplessness, her rage, and how she managed to transform all of it into art.

For me, what separates journal writing from essays are emotion, perspective, and structure. The essay is an invitation to mine emotion and experience to determine what could be used in a story that attaches itself to larger ideas, themes.

Journal writing tends to focus on me, me, me, and rightfully so. Emotions are raw, unfiltered, and in the moment. The pacing is fast and furious because the stakes feel high even if they’re not in retrospect. Think of any event in your life and how it felt all-consuming, and think about how you felt about that event months or years later when it’s cooled.

Journaling in itself has a verve because you’re writing about how you feel about a situation while it’s happening. And while that charged writing can be useful, essays benefit most from distance, perspective, and a small dose of emotional detachment.

For example, I wrote an essay recently that was dark. I was writing about a time nearly 25 years ago (distance). The impetus for the essay was a distinct memory of a cat drowning. And while the writing feels charged because I’m remembering the events and how I felt at that time, there’s an element of control because I’m removed from the events. You may think I’m sad while you’re reading it, but I’m not because the sadness and pain where experienced long ago. This essay simply revisits them. While writing the essay, I thought of other times we had pets, the events that lead to their demise, and how I could forge connections between these moments in time. Never would I have had that ability if I was writing in the moment because emotion clouds clarity.

Time, distance, and perspective give a kind of clarity that makes for powerful essay writing.

Essays allow the reader to step back and observe the situation or event from multiple points-of-view. Emotions are not as prevalent and loud and you consider all sides of a situation. You consider how past experiences affected the situation and the writing can be imbued with a perspective that feels wider and richer.

For me, journaling a place where you mine the events (and accuracy of them) and emotion, lift up the key components of a narrative to then mold them into an essay that shifts the perspective from me/I to me/you. Journaling is an act of voyeurism for the reader because they are given trespass to the most intimate and raw parts of your life while essays are an invitation to insert their experiences in the story.

You can manipulate the structure in essays because of distance and perspective. In the aforementioned essay, I move through a span of ten years — back and forth in time because I used one event (a cat drowning) to make connections between other related events — all of which to understand my mother (a lifelong pursuit), my childhood with her, and who I am as a result of the two. Journaling is more linear because it’s en media res. It’s immediate, now, whereas essays allow for a mixture of now and then (past and future).

Finally, essays allow for playing with language, tone, and style — elements of which you’re not considering in journaling because you’re not writing for an audience, you’re writing for you. And in that there’s no need for performance. There’s no need for flowery writing — there’s a need to document, to commit an event or emotion to paper. Essays allow you to mine that material (the what) and consider how you tell a story. How you can compose scenes, characters, and images that are larger than the events in and of themselves.

Consider Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy,” one of her most favorite poems. The poem is her obsession with her father, who died at an early age, and how his death impacted her and the men she chooses in her life. In the poem she makes several references to Nazi Germany (her father’s German), Dachau, his Aryan eye and brutish build. If you’ve read Plath’s journals, she doesn’t compose these allusions and images about her father — she merely writes about his loss and how it makes her feel. Poetry allows her space for perspective to make those connections and elevate the events in her life to something larger than a reader could understand or relate to.

This is not to say you have to make allusions to Nazi Germany in your work — I don’t, of course. However, I use song lyrics and cultural events and references to bring the reader in. When I write about the 80s and 90s I create a landscape so that the reader can feel transported back in time. My goal is to remove the reader from the now, from their phone, from all distractions, and take them on a short journey. A song or image I create may invoke something in them and now they’re invested because I’ve tapped into their nostalgia, something they can relate to even if they can’t relate to the events in my life.

While I was writing journals as a child and teenager, I didn’t care about landscape, imagery — all that jazz — I cared about what happened and how I felt. It’s only later that I’m able to look at that time and document all the things surrounding the events that make a story richer.

I see a lot of journal writing passed off as prose online. And perhaps I’m old-school but I think some of the raw elements of ourselves are best served off-line. We live in an age where every bit of our lives are documented and while there’s positives to creating, sharing, and connecting, there’s the element of giving away parts of yourself to strangers before you’re emotionally ready. You now open yourself up to criticism and perspective before you’ve even had a chance to process the events and that creates noise.

I’ve been guilty of writing rage blackout posts/journals here — most of which I’ve now deleted because they’re cringe when I revisit them. What I have done is taken those events and reworked them into essay form. I’m learning that the most private parts of my life can be still me mine if I leave them off-line. And when I’m ready, I can elevate those experiences into art and share them with readers so they can be part of the story when I’ve had emotional distance from it.

Outstanding! Some of my journal entries will remain just that - a journal entry and highly personal. But other entries did morph into something more and grew far-reaching tentacles that had me sit back and think, "What the.... where did that come from?"

Thanks for keeping me reaching to be better.

Love, love, love this! Another one for me to print out and save forever! 😊